Exclusive: Connectome Pioneer Sebastian Seung Is Building A Digital Brain

Meet Memazing

On a Sunday evening earlier this month, a Stanford professor held a salon at her home near the university’s campus. The main topic for the event was “synthesizing consciousness through neuroscience,” and the home filled with dozens of people, including artificial intelligence researchers, doctors, neuroscientists, philosophers and a former monk, eager to discuss the current collision between new AI and biological tools and how we might identify the arrival of a digital consciousness.

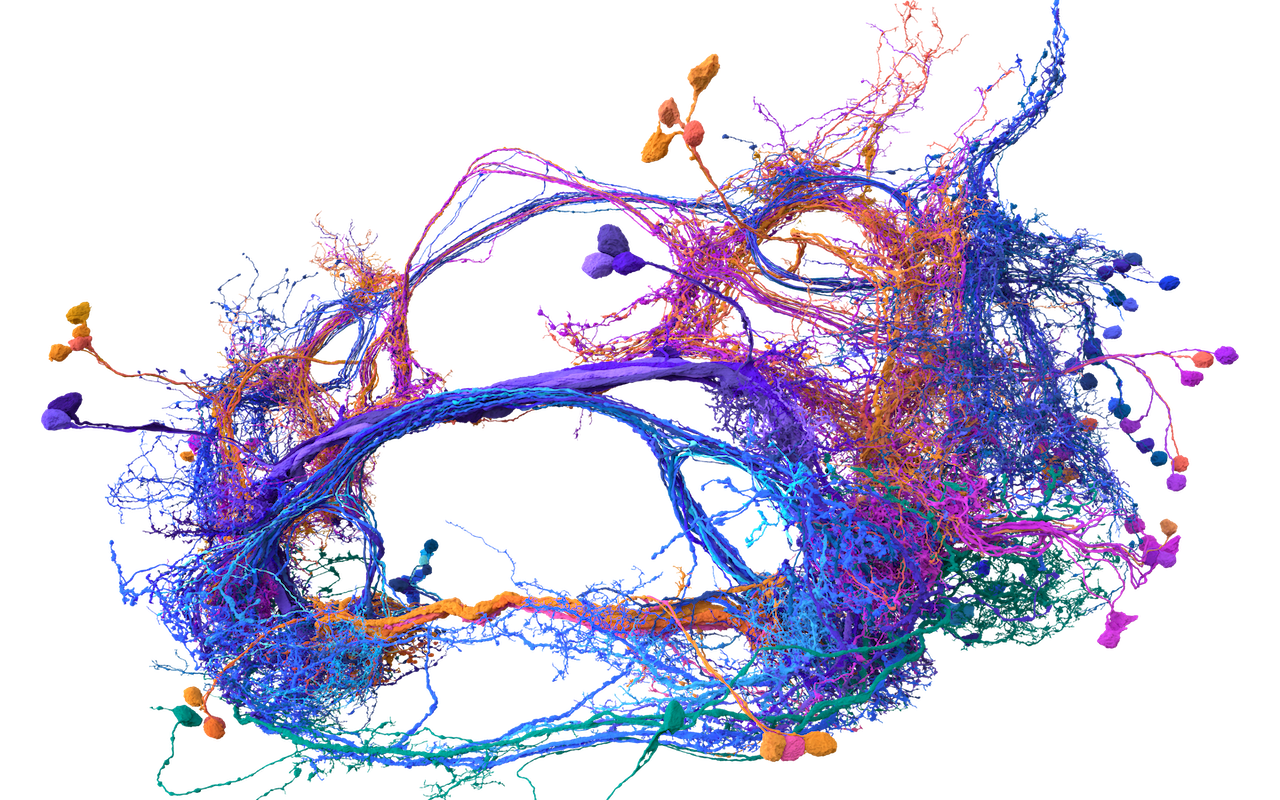

The opening speaker for the salon was Sebastian Seung, and this made a lot of sense. Seung, a neuroscience and computer science professor at Princeton University, has spent much of the last year enjoying the afterglow of his (and others’) breakthrough research describing the inner workings of the fly brain. Seung, you see, helped create the first complete wiring diagram of a fly brain and its 140,000 neurons and 55 million synapses. (Nature put out a special issue last October to document the achievement and its implications.) This diagram, known as a connectome, took more than a decade to finish and stands as the most detailed look at the most complex whole brain ever produced.

During his talk, Seung presented some slides showing the fly connectome (they’re beautiful images) and discussed what scientists have started to learn about the brain with this map in hand. We’ve already discovered new types of neurons and novel patterns uniting form and function in the brain. Researchers have also started to recreate the connectome in software to run simulations of fly brain behavior. The adult female Drosophila used to make the connectome has become a major point of scientific focus and something of a neuroscience celebrity. “My joke is that one fly died for this map, but this is the first fly that will live forever,” Seung told the salon crowd.

What Seung did not reveal to the audience is that the fly connectome has given rise to his own new neuroscience journey. This week, he’s unveiling a start-up called Memazing, as we can exclusively report. The new company seeks to create the technology needed to reverse engineer the fly brain (and eventually even more complex brains) and create full recreations – or emulations, as Seung calls them - of the brain in software.

(Seung says the Memazing name is a play on “amazing memory” and the idea that the connectome is the “me maze” in the sense that our thoughts memories are built and stored in the maze of synaptic connections.)

Seung contends that he’s chasing a new approach to understanding the nature of intelligence that’s in many ways opposite to the AI models that have arisen over the past few years. The AI models feed tens of thousands of processors with examples of intelligent behavior – such as huge volumes of text – and then tune the strengths of the relationships between the processors through repeated statistical optimization until intelligent behavior emerges.

Memazing, by contrast, has an existing map of how nature has produced intelligence over the course of millions of years of fine-tuning. It can see the strengths of the connections between neurons. Seung has already taken that information, inputted it into a computer model with great precision and begun to run experiments on that digital brain to see if he can stimulate the emulation and have it act like a real brain.

“We know that flies can see motion, run away from large objects and navigate,” Seung says. “We have to put the synapse counts in as weights and find out which other parameters we have to fiddle with in order to get the right actions to come out.

“If we did the simulation right, then hopefully intelligence will emerge.”

It’s early days for Memazing. Seung has assembled a team of a few people and is currently in the process of raising funds for his new venture. He’s also not alone. Over the past few weeks, I’ve caught word of at least two other connectome specialists hoping to spin up new companies that also want to use the fly data to try and build digital minds.

Whether this approach to engineering intelligence results in something spectacular is anyone’s guess. The people chasing this type of work, though, are hoping that knowledge gleaned from animal brains could translate into better AI systems. Animal brains, fed by a relatively small number of calories, remain far more efficient at processing information than the massive data centers fueling AI models. Perhaps emulating the fly brain will help unlock more clues about how animal brains do their work so well.

“The cost of AI has a lot of important implications,” Seung says. “It’s the difference between an AI that’s really centralized and requires a huge amount of investment and is controlled by a few corporations as opposed to AI everywhere. Intelligence too cheap to meter, right? I think slashing the cost of AI is one of the big motivations for us right now.”

On another front, people argue that understanding animal brains better could allow us to create tighter alignment between human and artificial intelligences. We could somehow bake humanness into AIs, and the AIs would then be more inclined to work with us instead of against us. More on the sci-fi spectrum, a number of people hope that the creation of these digitized brains could make it more feasible to upload minds into silicon substrates so that we might, well, live forever.

“The ultimate goal, of course, is to enable and power humanity to transcend biology,” Seung says. “So human brain emulation is the ultimate goal of the quest.”

Scientists created a full connectome of a worm brain about 40 years ago. It took decades to produce a connectome for the more complex fly brain, in part, because of the painstaking nature of the work. Connectomes are built by shaving off incredibly thin slices of brains, imaging the slices under electron microscopes and then reassembling the images via software into 3D models. Once you have the model, you then must trace and label the wiring of neurons and synapses, which is another brutal task. The human brain, for example, has millions of miles of wiring compacted into a skull-sized case, and you have to make sense of that entangled mess and produce a readable map.

Seung and his team pioneered a number of techniques to use AI software to help label the neurons and synapses of the fly brain. Several start-ups and research organizations are now trying to develop new imaging and labeling techniques in a bid to make building maps of things like mouse and human brains easier. Seung hopes that this influx of new data will accelerate his own work, although it’s possible that the fly connectome could provide enough information to make great leaps forward.

“Ideally, we’ll get human brain emulation when the human connectome is done,” he says. “But it could be the case that we find the principles of brain emulation with small brains and scale them up.”

Seung and his team have already begun work on their fly brain emulation, and they have started connecting their model to a simple robotics system. Over time, they would like to stimulate their digitized brain and see if it produces the right physical reaction in their robots. If, for example, you mimic coming at the fly with a swatter, can you get the robot to try and fly away.

Kenneth Hayworth, a neuroscientist at the Janelia Research Campus, cautioned that Seung and others have a lot of effort ahead of them. “With the fruit fly, we really do have all the hooks that would be necessary to really understand it,” he says. “But I still think it’s a long way off. Neuroscience is extremely difficult. When you push up against experimentation, things tend to fall apart in weird ways. I think it will take quite some time to develop a full understanding of how the fruit fly works.”

That said, Hayworth encouraged this type of research and said it’s exactly where scientists should be going with the fly connectome in hand. “Drosophila is an excellent target for the type of basic neuroscience that we need,” he says. “We are on that long road to eventually understanding brains and to do mind uploading. It will succeed eventually, but it will take a long time – maybe a hundred years.”

Seung is accustomed to facing some measure of skepticism around his work. Neuroscientists spent years questioning the value of creating animal connectomes. The brain maps only capture a single moment in time of a dead animal. We would learn far more about how the brain works by observing its behavior in real-time, although such research is very hard to do in practice.

The creation of the fly connectome, however, has justified much of Seung’s faith in this field of study as all types of new insights about the brain have appeared over the past year. Seung expects that new data and new insights will come at a steady pace as advances in AI and neuroscience play off each other.

“The connectomes are scaling up, and the data from academic labs and start-ups is growing exponentially,” Seung said. “We’re going to have all this fuel in which to feed the brain emulations because of all this commercialization going on.”

I'm looking forward to more. I've emulated C elegans and successfully applied to several robots. I have emulated the Drosophila CNS and I've done several experiments. I am about to launch Dronesophila = using the Drosophila nervous system emulation and applying it to a quadcopter. I've always said this is the best approach to AGI and very happy to find better experts than myself digging into this as a capability to AGI.

https://www.connectomicagi.com