Exclusive: Fridge Magnet Medicine

Nonfiction Labs is engineering proteins that respond to magnetic fields and betting it can change how we treat cancer

Two hundred years ago, the strongest magnets on Earth were natural rocks prized as navigational curiosities known as lodestones. After that came electromagnets, permanent alloys, and eventually the “I <3 NYC” fridge magnet. In the span of a few generations, humans surrounded themselves with magnetic fields a hundred times stronger than anything life was accustomed to encountering. And yet, biology didn’t notice.

Not a single protein responds meaningfully to a magnet. Extensive safety studies confirm it: magnetic fields pass right through us, doing nothing, and leaving no permanent trace that they were ever there at all. For most purposes, this is reassuring. For Richard Fuisz and Maria Ingaramo, it was an opening.

Their company, Nonfiction Labs, is building a new class of drugs whose activity can be switched on or off by a magnetic field - something they’re calling “magnetotherapeutics.” The ultimate goal is to make something that works only on active tumors, while leaving healthy tissue alone, all controllable with a magnet outside of the body.

The foundation for all of this is a protein that didn’t exist until a few years ago.

Much of cancer drug development runs on the idea that cancer cells express distinct surface markers (antigens) that distinguish them from healthy cells. It’s a quick leap then to the idea that, with the right target, tumors can be hit while sparing healthy tissue. This logic shaped modern immunotherapy and delivered real successes: Herceptin, Rituximab, Keytruda.

But after two decades of hunting, we’ve picked most of the low-hanging fruit. The cancer antigens we’ve found tend to be flawed in predictable ways. Some are only present in a small minority of patients, making them too rare to matter broadly. Others are found in lots of patients, but most people don’t respond well to therapies against them. The last batch are targets that are both widespread and potent and great for treating cancer. But they usually come at the cost of devastating side effects, requiring life-saving interventions just to survive the treatment.

The most effective options can, in fact, kill patients. And so, better approaches are needed to control how and when a drug turns on if we’re to eliminate the downside of the last category of targets that are both powerful and ubiquitous.

Which is where Nonfiction Labs comes in.

THE IDEA of using magnets to control therapeutics isn’t new. Previous attempts fused magnetic iron particles to proteins of interest. These particles could be dragged around with an external magnet to concentrate a drug in one location, or you could use alternating magnetic fields to heat the particles and trigger some downstream effect.

It didn’t really work. The physics was shaky, the effects small, and early attempts were plagued by experimental problems. The field stalled.

There’s been some experimentation with ultrasound, too, whereby external devices are used to heat delivery vesicles enough to shake a drug payload loose. But even with the increased precision, the released drug still flows onward towards other healthy tissues. These approaches are mostly about controlling where a drug is dumped, but the harder problem is controlling when a drug is working.

Nonfiction Labs’ story didn’t start with cancer, but with more academic goals. While working at Calico Labs, Maria Ingaramo noticed that Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) showed a faint magnetic response – it glowed differently in the presence of a magnet. But this effect was so faint that others had likely dismissed it as noise.

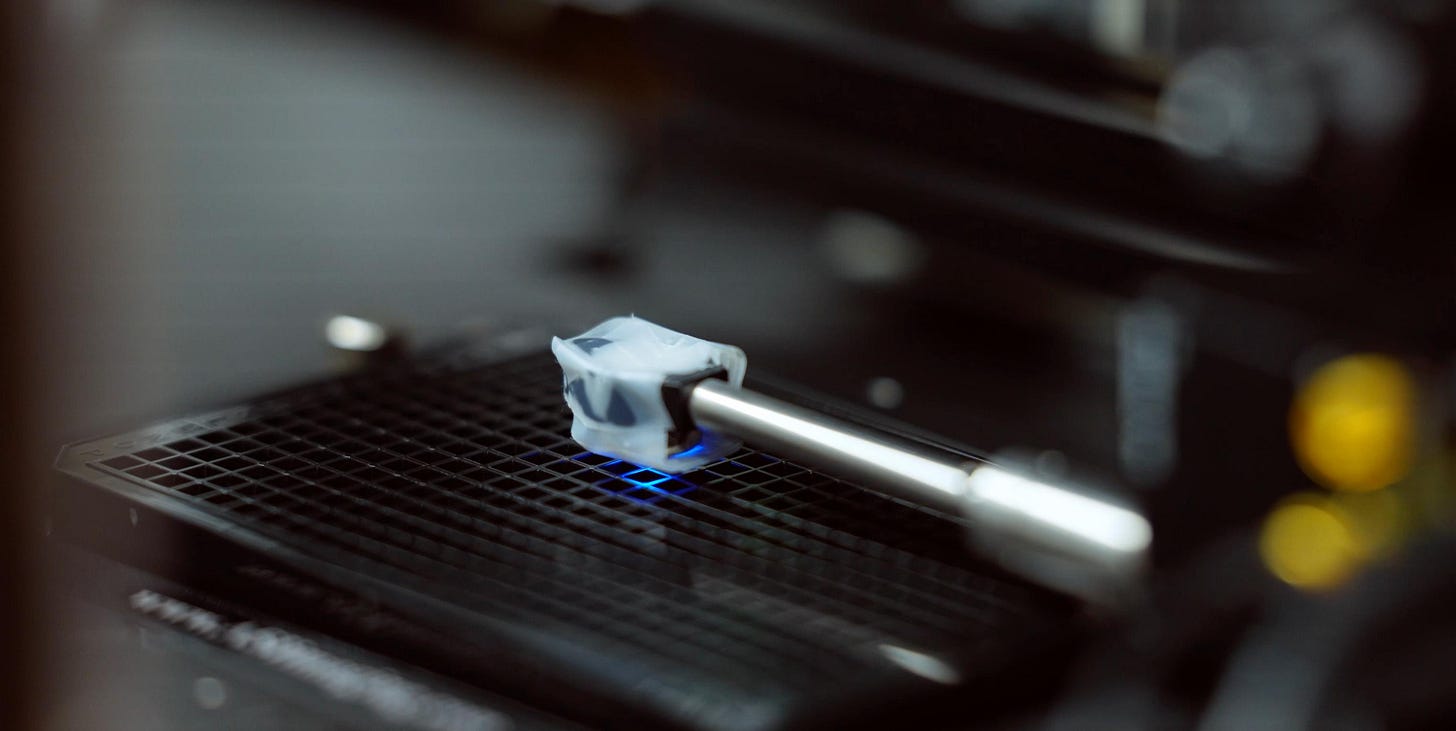

She spent a year prodding the protein with directed evolution, selecting for amplified responsiveness at every round, until she had a variant whose magnetic response was visible to the naked eye.

The mechanism is quantum mechanical: magnetic fields alter how electrons in the protein recombine after excitation, changing its fluorescence. The physics is cool, but secondary to the real lesson. Maria proved the effect is large, and it is engineerable.

Richard Fuisz met Maria back in 2021 while he was working on the early beginnings of what would become Arcadia Science before any of the magnetotherapeutics work began. When her experiments proved that proteins could be made to respond to magnets, his natural next question was - what else could be controlled this way?

The answer, it turns out, is antibodies.

Together they founded Nonfiction Labs and started building what they call magbodies. They’re basically Maria’s magnetically responsive protein parts stuck onto an antibody, where binding affinity shifts in response to a magnetic field. Apply the field, the binding weakens; remove it, binding kicks on. You end up with reversible, continuous control from outside the body. They’ve shown the trick works with enzymes too, gating catalytic activity magnetically.

This is all in service of breaking the constraint where the best targets have the worst safety profiles. A magbody therapeutic could circulate for weeks, inert, activating only where and when it’s needed. Local activation allows for safely hitting tumor cells at doses that would be lethal if engaged body-wide.

HER2 is a useful example. Herceptin, Kadcyla, and Enhertu are all FDA-approved drugs targeting this antigen, commonly found in breast cancers. All produce distinct toxicity because HER2 is also expressed in healthy tissue, particularly the heart. A magnetically controllable HER2 therapy could, in principle, be active at the tumor and silent in tissues prone to damage.

Despite the wins and cool prototyped glowing proteins, it’s still early days. The next milestones are taking things to animal models as part of the long slog towards bringing a brand-new cancer treatment into humans.

If this works, the implications go beyond oncology. Think immunosuppression that targets only a transplanted organ, or endometriosis treatments that hits pathological tissue while sparing the rest of the uterus. Drugs in the graveyard could get a second chance at life.

For billions of years, biology largely ignored magnets. But now, with some protein engineering, a sensitive optical rig and a year of intensive screening, that’s starting to change. Evolution may have missed magnets, but Nonfiction is betting medicine doesn’t have to.

(We also have a podcast between the author of this story and Fuisz right here, if you’d like to learn more.)

Magnets can also directly kill cancer cells, at least that's the premise of some investigated treatments, like the OncoMagnetic device

https://academic.oup.com/neuro-oncology/article/26/Supplement_8/viii117/7890671