Exclusive: The Spacecraft That Wouldn't Die

Epic Aerospace's record-setting tug has traveled millions of kilometers, and there's a chance we can bring it back

A cursed rocket took off on February 27th of last year. And it left us with a mystery that had gone unsolved . . . until now.

The rocket was a SpaceX Falcon 9. It launched from Florida and did what it was supposed to do. The problems arrived via the four payloads tucked inside of the rocket’s fairing. They were all meant to accomplish spectacular feats, although the space gods had other plans.

The most attention-grabbing payload was the Nova-C lunar lander from Intuitive Machines. It reached the moon a few days after launch but ended up on its side. The lander ran out of power a day later, and its mission ended.

NASA sent up a lunar craft of its own - the Lunar Trailblazer. It had been designed to orbit the moon and find and map the location of water on its surface. NASA, though, lost contact with the machine not long after launch and hasn’t been able to talk with it since.

AstroForge, the asteroid mining start-up, suffered a similar fate with its Odin demonstration craft. About a day after launch, the company lost contact with its machine. The last messages received from Odin came when it was 200,000km from Earth. The company tried to find solace in this accomplishment, saying that no private company had ever communicated with a craft that had traveled so far into space.

What AstroForge didn’t know at the time was that the communication record had already been broken by the fourth payload at the heart of our tale. This was Epic Aerospace’s Chimera GEO-1 – an orbital transfer vehicle (aka a space tug) attached to a satellite from an undisclosed company.

Unlike the other organizations with payloads on that Falcon 9, Epic has been quiet about the fate of its machine. Now, however, the company’s founder and CEO Ignacio Belieres Montero has come to Core Memory with a rather startling revelation. Chimera GEO-1 is 53 million kilometers from Earth . . . and it’s possibly alive . . . and Epic is hoping to try and bring it back.

The trick is that Epic will need aid from some mighty forces if it’s to pull off this daring and unprecedented feat.

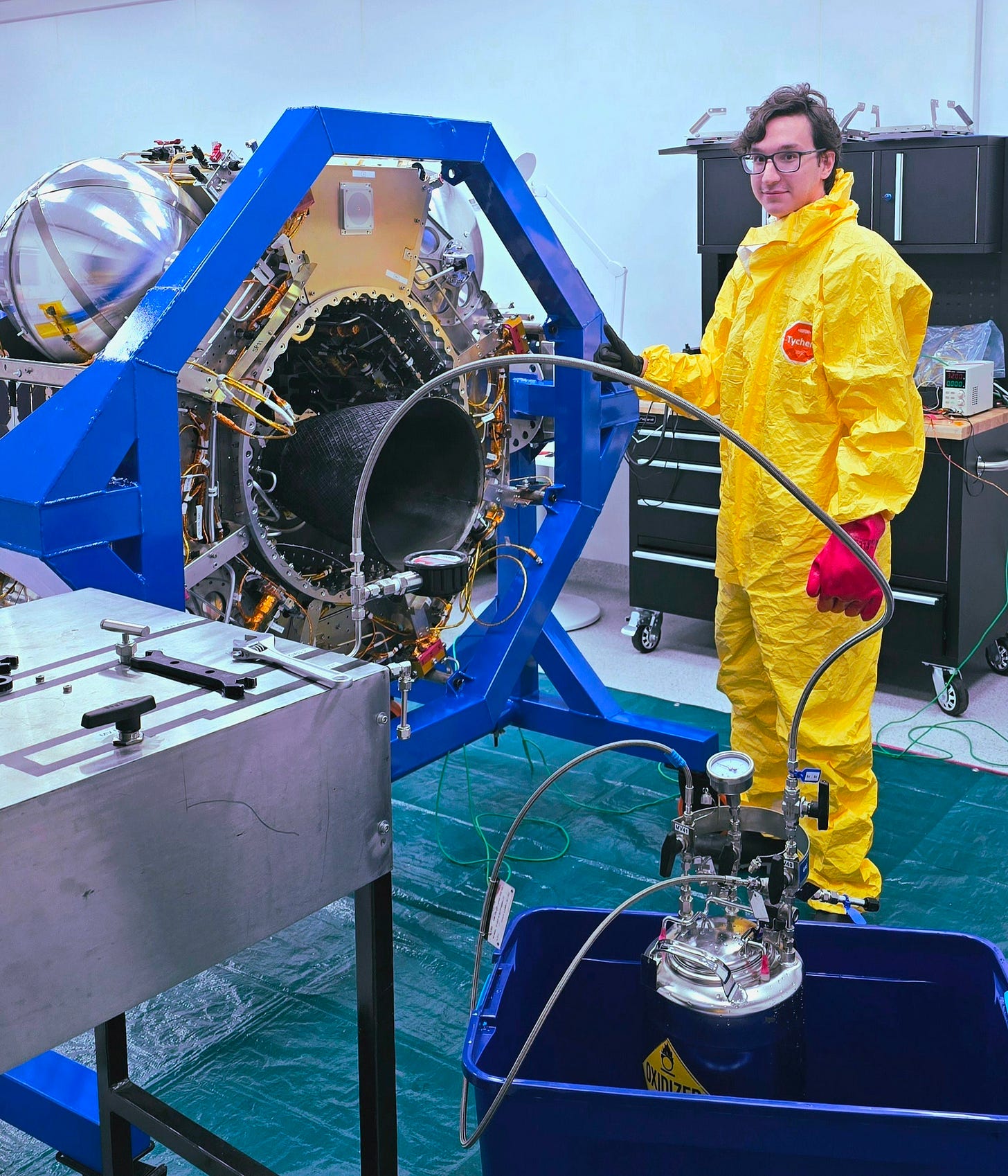

MONTERO IS in his late 20s and looks it. He’s fresh-faced with cheeks that push up high when he speaks and that punctuate the enthusiasm behind his words.

He’s from Buenos Aires, which does not usually come to mind as a major aerospace hub. Nonetheless, Montero became fascinated with rockets as a teenager after seeing a Falcon 9 launch webcast. One of those self-taught types, Montero began building his own rocket engines in high school, starting with solid rocket motors and then moving on to liquid-fueled engines. “I would build them and then do a lot of blowing shit up in random places throughout the Buenos Aires province,” he said.

Montero got into Stanford University in 2016 and set off to pursue a degree in aerospace and astronautical engineering. Well, truth be told, he set off to start a company and figured he’d use Stanford to make connections and eventually find some investors. During his first year on campus, he continued working on rocket engine designs – first in his dorm room (until a Resident Assistant narced on him) and then in the school’s machine shop (until the Dean of Engineering narced on him). “I ended up being told that I couldn’t build anything on campus and just had to study,” he said. (Well done, Stanford – Ed.)

Around 2016, the aerospace industry was in a boom cycle. SpaceX had inspired a new generation of rocket start-ups and a new generation of satellite start-ups to come into existence. The buzz and funding, though, didn’t do Montero much good. Most of the action was taking place in the U.S. and federal laws make it difficult for foreigners to take on major engineering work at American aerospace companies. Montero saw a space renaissance coming and decided his prospects at Stanford and in the U.S. were too limited. So, he dropped out and plotted a new path forward.

Like any good, young rocket engineer, Montero first decamped to the Mojave Desert to prove his mettle. He took some funds that were meant to pay for his housing at Stanford (without his parents knowing) and put them toward making a 2,000-pound thrust liquid rocket engine. The first three attempts to fire the engine failed, but, after months of toil, the fourth attempt succeeded. Montero secured his engine to a test stand, lit it, let it burn and then shut it down.

Convinced that he might know what he was doing, Montero returned to Buenos Aires and started a company in 2017 with a perfectly ambitious name – Epic Aerospace. He flirted for a moment with trying to get into the rocket business but then decided it would be too costly to compete with the likes of SpaceX and Rocket Lab. Instead, Montero opted to focus Epic on becoming a key part of an ever-expanding space infrastructure. He would build machines that move other machines to their desired orbits.

One reason a company like Epic would make sense could be traced back to SpaceX’s rideshare program. Sometimes SpaceX sells a whole rocket to a single customer. Over the past few years, however, SpaceX has also been allowing numerous customers to share spots on a rocket by packing multiple payloads on a single Falcon 9. The rocket goes up, opens its fairing and out pop the payloads, be they satellites or other spacecraft. The upside of this approach is that it lets companies and organizations split the cost of a rocket launch, meaning they can get to space more cheaply. The downside is that not every payload gets dropped off in its ideal orbit. Think taking a bus that lets you off at a designated spot instead of a car that takes you right home.

The spacecraft makers can deal with these issues by putting small engines on their satellites. The engines fire while in space and adjust the orbit. But not every company or organization has the money or know-how to handle these operations. And so, a company like Epic makes the equivalent of a space tug. It attaches to a satellite or other craft and uses an engine on the tug to push the other machines around as needed.

Montero was betting that SpaceX’s rideshare program would be a big success and that companies and governments were poised to start sending satellites up by the thousands. This big increase in things going to space and needing to be in the right place could create a lot of demand for space tugs. And Montero’s bets would prove correct.

ARGENTINA MIGHT not have a reputation as a space superpower, but it does have a space agency with a string of successes constructing satellites for Earth observation, communications and science. The country has quietly built up the heritage and infrastructure needed to go all the way from design to build and test and in-space action. Once you get past the heavies like the U.S., China, Russia, Japan and India, Argentina stands out as an overachiever.

Via his pluck and guile, Montero had gotten to know a number of the Argentinian satellite engineers and government players. He recruited a handful of them to join Epic and buy into his vision. In 2019, the company managed to raise its first round of funding and put $1.1 million in the bank.

Just a couple of months after raising the money, Epic began building a rocket engine test stand near the airport in Buenos Aires. It also started concocting its own propellant for the engines. Epic chose hydrogen peroxide, which is notoriously dangerous because it looks like water (harmless) but has a habit of exploding at inconvenient times (less harmless). You also cannot buy hydrogen peroxide at the necessary concentrations, and so, Epic had to learn how to refine its propellant in significant volumes.

By November of 2019, Epic was ready to test its first engine. Naturally, it blew up. Over the next year, though, Epic made remarkable progress and completed more than 100 engine tests. These successes helped the company raise another $5 million, which, in turn, gave Epic enough money to build its first spacecraft called Chimera LEO 1.

Not really meant for a customer, Chimera LEO 1 served as an engineering test for Epic. Its small team built the 150kg vehicle in about a year as they raced to meet a deadline for a spot on a SpaceX launch. They took shortcuts on communications systems and internal electronics to save time and made the craft out of the proverbial glue and duct tape. It did not launch until January of 2023 because of delays with the rocket, and Epic struggled to communicate with the vehicle once it reached space. Still, the company’s engineers gained experience and felt confident that they were heading in the right direction.

And that brings us to the star of the show: Chimera GEO-1, which Epic started building in July of 2023.

AS THE NAME indicates, Chimera GEO-1 was a space tug meant to push a satellite around into a geostationary orbit about 35,000km from Earth. The craft was roughly shaped like an octagon with solar panels around its sides, an engine on its bottom and antennas and other communication equipment dotting its body. It could support a satellite payload of up to 300kg.

Since Epic had struggled to communicate with its first vehicle, it packed its second try with redundancy everywhere – extra radios, extra battery packs, extra power systems, extra computers, and two star trackers. It also performed tons of testing on all the components. Montero personally inspected every cable and connection on the spacecraft. “There was essentially two of everything and redundant wiring in every single freaking place,” Montero said.

The craft also had plenty of solar panels and could survive on very low power. “We designed it to be kind of unkillable,” Montero said. And this would prove quite fortuitous in the months ahead.

Epic moved fast with its work. It had a completed spacecraft by April of 2024, which it could then test as a full system for several months before shipping the vehicle via air freight to the U.S. near the end of the year. Once stateside, Epic had to meet SpaceX’s requirements for fueling the spacecraft and mating it with the Falcon rocket. There were some stumbles along the way. Montero, for example, had passport issues and wasn’t allowed near his prized possession for a couple of days. Still, Epic and its tiny team met one deadline after another.

The company’s plan, should all go well, was to execute a handful of thruster burns over the course of two weeks, aim its satellite payload toward the right spot and then have Chimera GEO-1 separate from the satellite and head to a graveyard orbit (where the tug could hang for hundreds or thousands of years out of the way of other stuff) 300km above GEO. Easy.

Ahead of the launch, however, things began getting tricky fast. Intuitive’s lunar lander was the star of the show and had priority around the drop-off orbit for the payloads. Epic had been designing its mission for one drop-off point only to find out relatively late that it would be dropped off somewhere else altogether. This change brought with it major ramifications for the flight path of the Chimera GEO-1. Montero and his team realized they might now need to do an extra burn and execute it in a tight time window to prevent the Chimera GEO-1 from being hurtled out into space.

SpaceX’s rocket took off on February 27th, and reached space a few minutes later where its fairing opened and began plopping out the payloads. Shortly thereafter, Epic received a message from SpaceX telling it where and at what velocity Chimera GEO-1 had been dropped off. From there, Epic began trying to communicate with its spacecraft and to figure out what sort of maneuvers it would need to complete.

It did not take long for things to start going really wrong.

EPIC HAD teamed up with two ground station providers to help with the communications for the launch - one with two 11m diameter ground stations in both Australia and Chile, and the other with a single 30m diameter ground station in New Zealand. The New Zealand backup station suffered a power outage right as the launch countdown began.

An hour into the mission, Epic managed to decode some telemetry and check on the health of its craft’s batteries, computers and radios via the ground station in Australia. Two hours in, though, as more telemetry came in from the Australia site, it became clear that the vehicle was alive and well, but it was not receiving commands properly for some reason. It was as though Chimera could talk but not hear.

Six hours into the mission, the spacecraft had reached 80,000km from Earth, and Epic’s team had managed to unreliably send up a couple of commands. But, with the spacecraft now setting over the horizon in Australia, they were in the process of losing their means of speaking with Chimera GEO-1.

“We’re trying every single thing we can because it’s actually quite hard to communicate with a spacecraft that’s flying off essentially towards the moon at kilometers per second with significant doppler shift and with very tight pointing accuracy required on the ground,” Montero said. “There are multiple things that can be wrong. You could be using the wrong modulation or bit rate or even have something as stupid as having a supplier forget to turn on a radio transmitter on the ground.”

Montero could quickly tell that Epic had an arduous adventure ahead of it. The company desperately needed to speak with its spacecraft, and there was every chance that the machine was in peril of heading aimlessly into space. Being a small company, Epic did not have multiple teams to deal with many hours or even days of trouble shooting. It was up to a handful of people in a makeshift Buenos Aires command and control center with some air mattresses to problem solve and endure.

Over the next 24 hours, Epic hopped from ground stations in Chile and Australia to amateur stations in Germany, looking for anyone that could help it speak to its spacecraft. Little by little, they managed to zero in on the problem, discovering an unlikely incompatibility between their transmissions and the ground station hardware. Their hardware supplier began cobbling together a fix as best as they could.

Thirty-six hours in, the first set of reliable commands were sent to the vehicle. But, with the spacecraft now over 240,000km from Earth, panic had begun to set in for Montero.

The ground stations Epic had been working with had been expected to reach their limit at 200,000km, and the team could see no way they would be able to talk to Chimera farther than the 240,000km where they had just eeked out chatter on their last pass from Australia.

Montero realized he’d need to find a bigger dish and fast.

He began calling the Argentinian and European space agencies, seeking help. He also tried contacting other companies with payloads on the Falcon 9 to try and borrow their ground stations. “I would say, ‘Hey, my name is Ignacio. I’m the CEO and founder of Epic Aerospace. I’m having a spacecraft emergency,’” Montero said. “I read online that these were the magic words to reach someone that can actually help.”

People soon directed Epic toward Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station in Cornwall, England. They have a reputation as helpful space communications mercenaries who will do just about anything for the right price. Goonhilly, however, was already working with Intuitive and making sure that its lunar landing went well was their main objective. Still, on day three of its mission, Epic was allowed a small window to communicate with its craft, and things actually worked! Epic made contact on the 30m dish and was able to send commands to the spacecraft. For the first time, it seemed like progress had been made. “It felt like we had something of a solid Wi-Fi connection to it,” Montero said.

Racing against the clock, the Epic team worked to turn on and test the star trackers and inertial measurement units on their craft. These are the critical sensors that tell the spacecraft where it’s pointed in space. After a series of new technical issues and many unforced errors, however, it soon became clear that Epic would not have enough time to get everything in working order.

Without commissioning these sensors, there would be no telling which way the spacecraft was pointed in space and certainly no engine burn to bring it back. Epic’s engineers used the last few remaining minutes of their Goonhilly pass to send a software update that would let them manually control the craft’s thrusters from the ground - a last-ditch attempt to let them adjust the spacecraft’s attitude without relying on the star trackers or IMUs in the future.

As Goonhilly moved on to support Intuitive’s lander, Epic monitored telemetry coming in from an amateur station in Germany to see if everything was still fine. And then, after 30 minutes, the spacecraft went dark. Puzzled, Montero and the other engineers looked at their screens trying to understand what happened. “Did we blow it up somehow?” they wondered.

On March 6th, Intuitive’s lander tipped over on the Moon. This was fortunate for Epic because it freed up Goonhilly. That said, things were not looking great for the Chimera GEO-1. It had flown past the Moon, was now 340,000km from Earth, and it had also been completely silent since the last contact.

OVER THE NEXT MONTH, Montero and Epic set out on a frenetic quest to try and have a dialogue with their machine even as it raced away, making such communications harder and harder. Epic began working with Goonhilly and Parkes Observatory in Australia. Together, they spent hours on end sending commands and watching out for replies to see what was alive on the machine by trying to make sense of the shape and strength of the signals coming out of the spacecraft. Epic wanted something – anything! – positive to report back to its customer, and its engineers desperately wanted to know if their hardware actually worked in space. The spacecraft was now 600,000km from Earth.

In a bid to find more help and ever better signal strength, Montero hopped on a flight to Germany and turned up unannounced at Effelsberg Radio Observatory, which has a 100m, steerable dish, the second largest steerable dish in the world. “I landed in Frankfurt, rented a car, used the Autobahn to its fullest extent, arrived at Effelsberg and just started ringing the bell,” Montero said. “I told them that I had a spacecraft emergency and needed urgent support.”

When no one answered, Montero took a nap in his car right by the entrance gate. Later, he managed to catch the station manager’s attention and was let in to use the station. But, as the men dug into the situation, it didn’t seem that even a 100m dish would be powerful enough to do what Epic needed.

By the start of April, the spacecraft was 1,000,000km away. Montero and his team had been working the problem all the while. They had a stroke of luck when the spacecraft, by pure chance, reset itself. As with all major computer problems, this simple act had returned the vehicle to a more pliable state.

Working again with Goonhilly, Epic finally managed to decode some telemetry data, which allowed them to not just send but also receive other data with ease. Epic quickly turned to testing the star trackers, inertial measurement units, and then valves that would be required for the spacecraft to be able to control its direction and eventually its engine. The more Epic fiddled, the more they discovered that a large software update would be needed that would give the ship enough smarts to operate independently so far away from home.

The update proved challenging. A small test file here and there would always be followed by the inevitable realization that something was missing (or had been screwed up) with the upload. They came to realize that the software would have to be rebuilt from the ground up to deal with the long trip times, a spinning spacecraft, and marginal communications. The engineers worked to strip the software down to its barebones, trying to find creative ways to alter programs and feed them straight into the computer’s memory, much like NASA once saved Voyager 1.

This pattern went on for months. Montero became a ground station master, meeting everyone possible and begging for help and wisdom. All the while, the spacecraft kept traveling farther and farther away – two million kilometers by the end of April, eight million kilometers by the end of May and 15 million kilometers by the end June. Ground stations would go in and out of operation. Some would even catch on fire. And, all the while, Epic would get just enough of the software and hardware tested to convince its team that they could still bring the craft back if they just had a better signal and enough time to turn the engines on.

By September, with their craft more than 33 million kilometers away, Montero and his team had managed to do almost the impossible. After pulling some strings, they had gotten a trial run with a much more powerful antenna for the first time, and finally got to test the new smarts they’d given their little craft. They managed to point Chimera in the right direction, warm it up, pressurize the propulsion system, and run through all through their last check items to show the vehicle was ready to rumble.

WHAT MONTERO really wants now is access to large deep space antennas run by NASA and ESA. Epic wants to issue some commands that would align the tug in the right direction and fire its engine. Montero believes it would take about a year for the vehicle to make its way 53 million kilometers and counting back to Earth.

The large agencies, though, have been reluctant to help Epic out. It’s a commercial mission instead of a science mission and would require some tending (Epic thinks just a couple of days) to support. Epic could use some of the traditional American and European nationalistic space sympathies to get people behind its quest. But until some important people embrace what saving the Chimera GEO-1 means in the big picture, the company and its tug will remain caught in the void. (Epic, of course, is already racing ahead with new customers and its next missions.)

“My job recently has been to find a way to get this new checkbox checked, and to get them and others to see that they can and should support us going forward,” Montero said. “Maybe to do this I will have to take some sort of detour on our way back home and take pictures of another planet, or an asteroid, or learn and show how we - and other missions - can navigate in deep space using minimal tools.” In other words, he might need to turn this into a science project.

Over the past year, Montero has shaken his fists at the heavens and searched his soul. He’s gone without sleep and food and been on the edge of sanity. He’s desperate to prove Epic’s technical chops and that he’ll do just about anything for a customer. Mostly, he’s a man possessed.

“I remember cursing at the tug just before a pass, looking at the midnight sky, as many of the guys on our team probably did, and repeating to myself and the tug, ‘I’m going to bring you back. I don’t fucking care if you want me to or not, but I’m going to bring you back,’” Montero said.

Jared Isaacmam, let's make it happen!!

What an extraordinary young man Monero is!