The Abyss Opens For Business

The messy fight over the critical mineral fortune buried beneath Earth’s last frontier

In 2021, a remotely controlled vehicle set out to probe a darkness billions of years old, streaming a camera feed up to Dr. Andrew Sweetman and his team huddled aboard the Maersk Launcher. The Welsh scientist advised his colleagues to keep their eyes locked on the screen, for even a single moment away could mean missing a creature no human had ever seen before.

The researchers had company, in an almost literal sense. There were business interests onboard. And what united the suits and the scientists in this moment wasn’t the prospect of spotting new life, but studying the inanimate. After all, the objects found down here, thousands of meters deep, have the potential to change the economics of an entire industry or two and alter the political landscape between the U.S. and China.

Beneath the brittle stars and gummy squirrels of the ocean’s abyssal zone lie a vast expanse of fist-sized rocks, called polymetallic nodules. Though found across many ocean basins, the richest deposit of nodules exists in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a 1.7 million square-mile stretch of Pacific seafloor that, thanks to the nodules, contains more nickel, manganese, and cobalt than the entire terrestrial reserve base.

If Dr. Sweetman cared about the CCZ’s economic implications, he didn’t show it. Three years after his voyage into the zone, his team published evidence revealing that the unique metallic composition of these nodules creates oxygen, a process formerly believed to be possible only through photosynthesis. The presence of “dark oxygen” would raise new questions about where aerobic life began on Earth and even where we might find species beyond our planet. In other words, a big deal.

This discovery and the reaction that followed highlighted the tension and complexity that surround the nodule riches within the CCZ. The Maersk Launcher is owned by The Metals Company (TMC), a NASDAQ-listed venture seeking to harvest these nodules for the critical minerals and rare earths they contain. As part of their mandate to explore and possibly mine the seafloor, TMC must hire scientists like Dr. Sweetman to conduct independent research. But what those scientists publish can impact where, when, or if private companies can extract resources from the last remaining part of the Earth that no one owns. Not long after Dr. Sweetman released his research, TMC issued a rebuttal refuting the “dark oxygen” findings altogether.

These scientific debates run alongside legal squabbles that are moving too slowly for industry or the U.S. government to tolerate. There’s a growing fleet of commercial, nodule-harvesting ships currently operating on exploration licenses granted by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a quasi-UN body that regulates all oceanic mining activities beyond national jurisdiction. Since 1994, the Jamaica-based group has been tasked with writing laws for its 170 Member States, but has yet to formalize any official guidelines on whether or when nodule farming can proceed in earnest.

The United States is one of the few countries excluded from this list. Instead, the US issues licenses on its own terms. Exactly what this regulatory conflict means for deep-sea mining has remained largely a gray area. But as the trade war with China escalates and demand for minerals grows, private companies are itching to deploy at a commercial scale. Amid these pressures, the US has forged ahead with plans to extract polymetallic nodules, international regulations be damned.

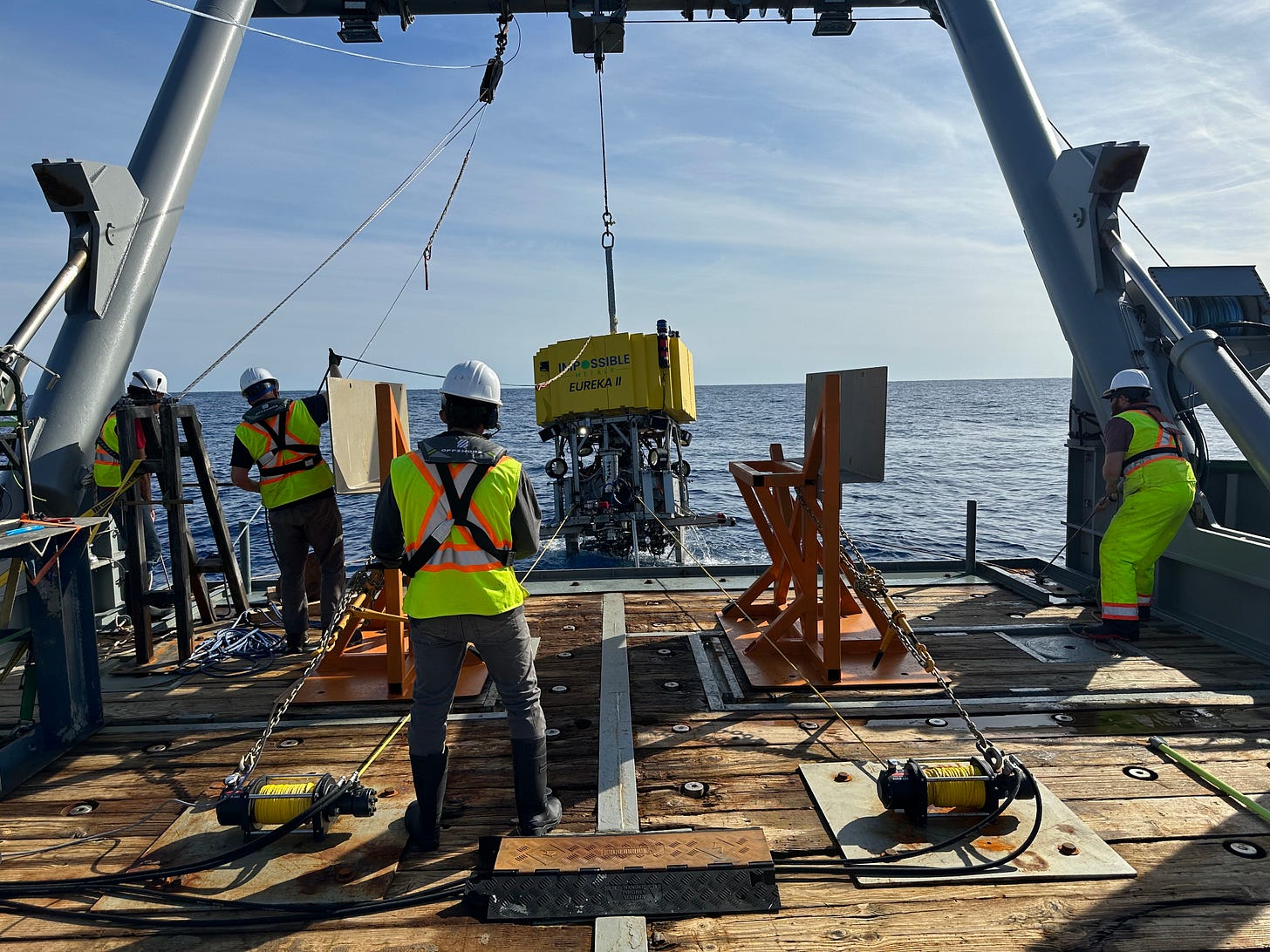

The Metals Company is the dominant player in the deep-sea mining industry, but an upstart called Impossible Metals is attempting to corner the market with less ecological intrusion. Both have submitted commercial operation requests to the United States last year after President Trump signed an executive order to unleash offshore resource extraction.

These mining companies present themselves as the lower-impact alternative to extracting the minerals critical to electrification via more traditional methods on land. They don’t need to tear up the Earth by excavating vast mines or subject people to labor in horrendous conditions. They must simply harvest the nodules sitting right atop the ocean floor. To critics, they’re trading one environmental catastrophe for another.

What they discover in the coming years will have profound scientific impacts for one of the least studied ecosystems on Earth. They will also answer the burning question of who actually owns the riches of the planet’s last frontier: humanity, or whoever gets there first?

IMPOSSIBLE METALS’ story begins in 2020 on an inauspicious lockdown day, when wildfires reddened the Bay Area’s sky, and Oliver Gunasekara sat indoors thinking about electrification. The British businessman was looking for a new venture after a career spent in semiconductors, and he figured that supplying the raw materials for battery manufacturers was a sound idea.