How an MIT-Trained Engineer and Rock Star Took On His Record Label — And Won

The saga of Tom Scholz, Boston and their magical music devices

Fifty years ago, the rock band Boston—spawned in the basement of an MIT-trained mechanical engineer named Tom Scholz—became one of the biggest moneymakers for the biggest record label in the country. With hits like “More than a Feeling,” and “Peace of Mind,” they were suddenly everywhere.

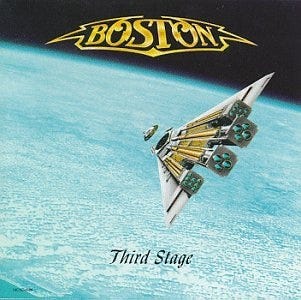

And then, just as suddenly, they weren’t. After his second album, Scholz withdrew from an industry he despised (“the lowest form of life” he called it) and ended up in an all-out war with his label, CBS Records. He had refused to turn over his third album, Third Stage, until it met his absurdly high standards. In this excerpt from Power Soak: Invention, Obsession, and the Pursuit of the Perfect Sound, journalist Brendan Borrell tells the story of how Scholz turned his studio-built inventions into a multi-million dollar company that changed the sound of 80s rock — and help sustain him during a seven-year legal fight.

Tom Scholz would have to decide whether to retreat or dig in, but he was prepared for anything. Quietly, almost without notice, he had been building a war chest. In a small shop above a hardware store near his home, he’d been spending sixty hours a week, working on a series of devices he had originally made for himself and his bandmates.

Some of these devices were meant for the studio; others were meant to help reproduce those studio sounds on stage. But circumstances had a way of escalating with Scholz, particularly when a soldering iron was involved.

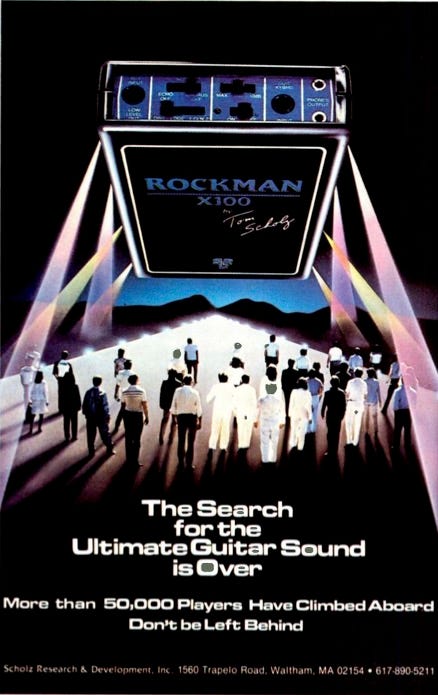

In the summer of 1982, he brought a prototype of one of his devices—a little black box that could fit in the glove compartment of his Datsun—to the National Association of Music Merchants’ annual expo in Atlanta. Booth #9042 was otherwise empty save for seven large Styrofoam letters painted to look like concrete: ROCKMAN.

Scholz picked up his guitar and handed the first curious visitor a pair of headphones. He strummed a few power chords. The man’s eyes widened in a way that suggested either awe or heart trouble. Scholz had managed to capture the searing distortion of his Marshall amp at full volume in this sandwich-sized box. Others gathered to try it, heads swaying to invisible music. Scholz’s coffee sat cooling beside him, untouched for hours.

Scholz Research & Development had its first hit.

Scholz knew that CBS might well see his new company as a distraction. His father did, too, asking him, with no hint of irony, why he was wasting time with engineering when he should be coming up with new songs. (He previously berated him for playing music when he should have been focused on engineering.)

But Scholz knew better than anyone that his mind wasn’t a machine. He was motivated by his time at Polaroid, when he devised the bridge for “Peace of Mind” in the middle of the workday, then came sprinting home to try it out on his guitar.

Scholz’s first product was a commercial version of another device, the Power Soak, which Scholz and his bandmates had been using for years. That was just a series of resistors that sat between the guitar amp and the speaker, skimming off the excess decibels and releasing the extra energy as heat. “You could put a piece of bread in there and make some toast,” joked Neil Miller, an engineer who worked at Scholz’s company.

The latest device, the Rockman, took the Power Soak idea a step further. Now that growl could be piped from the guitar directly to a mixing console or a pair of headphones—no amplifier needed. It simulated the harmonic distortion on a palm-sized circuit board.

When Scholz returned from Atlanta, the orders piled up. Guitar Center wanted a batch. So did Manny’s Music on 48thStreet in Manhattan. Elliott Easton, The Cars’ lead guitarist, who lived down the street from Scholz’s shop, picked one up in person and used it on his next album, Heartbeat City. Carlos Santana got one, so did Journey and Def Leppard. Joe Satriani, he got two. Todd Rundgren? Four, routed through a pedalboard.

Unlike the Power Soak, demand for the Rockman went beyond the professional community. Thousands of teenagers unwrapping Gibson guitars at Christmastime could now emulate their heroes on their home stereos. The company would soon be raking in over $6 million per year, easing Scholz’s financial worries. His wife Cindy helped run the place and Scholz gave her brother a job there, too, as executive vice president.

The Rockman enabled Scholz to buy time and pay his mounting legal bills, but it couldn’t finish an album for him. He wanted his music to be upbeat and inspiring, but he was feeling anything but. CBS had cut off his royalties, and his band was falling apart. Then, the company sued him and the bandmates for $20 million.

In early February 1984, Scholz had to sit for his first deposition: two days of grilling by CBS’s outside counsel at the offices of Moses & Singer in Manhattan.

Scholz was asked about his upbringing, his recording techniques, and even whether he received professional help for depression following his guitarist’s departure from the band. “No,” Scholz snapped back. “Do you when you are depressed?”

“Did you ever take lithium?” the lawyer asked.

“Don’t know what it is. I think it goes in batteries, doesn’t it?” he said.

“Sometimes it goes in people,” the lawyer said.

Scholz released Third Stage in 1986 with a competing label and won millions from CBS in court. His Rockman line was acquired by Dunlop in the 1990s. When his legendary analog circuitry was revived as a guitar pedal earlier this year, the first shipments quickly sold out at Guitar Center.

Excerpt from Power Soak © 2025 Brendan Borrell

Great piece! Boston (for better or worse) was the soundtrack of my youth. And Tom Scholz is an endlessly fascinating character worthy of a book. Just bought the Kindle book. Can't wait to read it.